I’ve been prosecuting warranty cases for a while now. A few years ago, I wrote a post about the Apple Warranty. Well, evidently someone out there read my post, because in January of 2020, a client called me to ask advice for how to deal with a defective iPhone. Here’s her story.

Back in October of 2019, she bought a brand new iPhone XR from the AT&T Store in Fairhope, Alabama. The iPhone cost her $649.99. She had been an iPhone user for years, and was loyal to the Apple brand. So she had every reason to expect that this new iPhone XR would function well.

She was wrong. From the time she purchased the iPhone, it frequently and unpredictably dropped calls, even when there was a perfectly good cellular signal available. Her reception in her home was great. Her husband was on the same AT&T cell phone plan as her, and his phone never dropped calls. Also, none of her previous iPhones had this problem, either. In addition to the dropped calls, her iPhone would frequently connect a call, but then unpredictably mute the audio. She estimates that about 1/3 to 1/2 of her calls either dropped or had muted audio.

No problem, she thought. I’ll just ask Apple to replace it or refund my money. Surely, as a longtime, loyal Apple customer, they would be glad to help, right? Not so.

First, she took the iPhone to the AT&T Store. There, they attempted to resolve the issue by resetting the phone and checking to make sure that it was properly receiving signals from the local cell phone towers. It was.

After several visits to the AT&T store failed to resolve the issues with the phone, she decided to call Apple. She called them in November 2019 and spoke with them, but they refused to offer a replacement or a refund. She called again in December 2019, and spoke to their agents for hours. But again, they refused to offer a replacement or a refund.

Unable to convince Apple to do the right thing, she called our office for help. We sued Apple on February 3, 2020, alleging breach of warranty, and asking for an award of damages, plus costs and attorneys’ fees pursuant to the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act.

The Magnuson Moss Warranty Act.

The Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act is a federal law passed in 1975 (signed by President Gerald Ford) which applies to all consumer products sold in interstate commerce that cost more than $15.00. The Act does a few things, but the most important ones are:

- Written warranties cannot give you less rights than implied warranties in the UCC or common law. 15 USC 2308

- Warrantors must, at a minimum, repair, replace, or refund a defective product within a reasonable time and at no charge. 15 USC 2304.

- Before filing a warranty lawsuit, the purchaser of the product must first notify the warrantor of the problem and give them a chance to remedy it. Also, if the warrantor has an informal dispute resolution mechanism in place, the purchaser must first follow that procedure before going to court. 15 USC 2310(a).

- If, however, the warrantor does not resolve the issue with the product, the purchaser can sue the warrantor for damages, and if you win, they have to pay your attorneys’ fees and court costs. 15 USC 2310(d).

“The provision for awarding attorney fees in Magnuson-Moss exists in order to assist consumers in vindicating their rights where legal expenses would otherwise be prohibitive.” Leavitt v. Monaco Coach Corp., (Mich. Ct. App. 2000). “Thus, the clear language of the Magnuson-Moss Act allows recovery of an attorney fee by a consumer who prevails in a breach-of-warranty action against a seller under state law, provided the seller is given an opportunity to cure.” Forest River, Inc. v. Posten, (Ala. Civ. App. 2002).

The Trial Against Apple.

When I told my dad I was suing Apple, he asked, “Aren’t you sort of scared to be going up against the biggest tech company in the world?” “Absolutely not,” I said. I knew that my client was telling the truth and that the law was on my side. When Apple answered the Complaint, they denied any wrongdoing. They said that they owed my client nothing because she had not “satisfied her obligations under the Warranty.” Before the trial, Apple filed a pretrial brief arguing that they had not been given the chance to fix the phone, and for that reason, they couldn’t be held liable for their own defective product.

Apple’s pretrial brief blamed everything on my client:

“When Plaintiff began having problems with her iPhone, she did not seek help from Apple. She did not bring her phone to an Apple store, and she did not seek to send it to Apple for warranty service.” Evans v. Apple, Inc. 05-DV-2020-900173, Document 49, p. 2. Turns out, this just wasn’t true. She called Apple more than once and all she wanted was a refund or a new phone. None of Apple’s employees ever even asked her to return the phone for repair. Nor did they send her a packing slip or any shipping instructions. And the nearest Apple Store is over 150 miles away!

In my own brief, I pointed out the fact that Apple could have easily just offered her a refund or a new phone. It was written right there in their own warranty. But they didn’t. The first time they asked for the chance to repair the iPhone was after we’d filed the lawsuit.

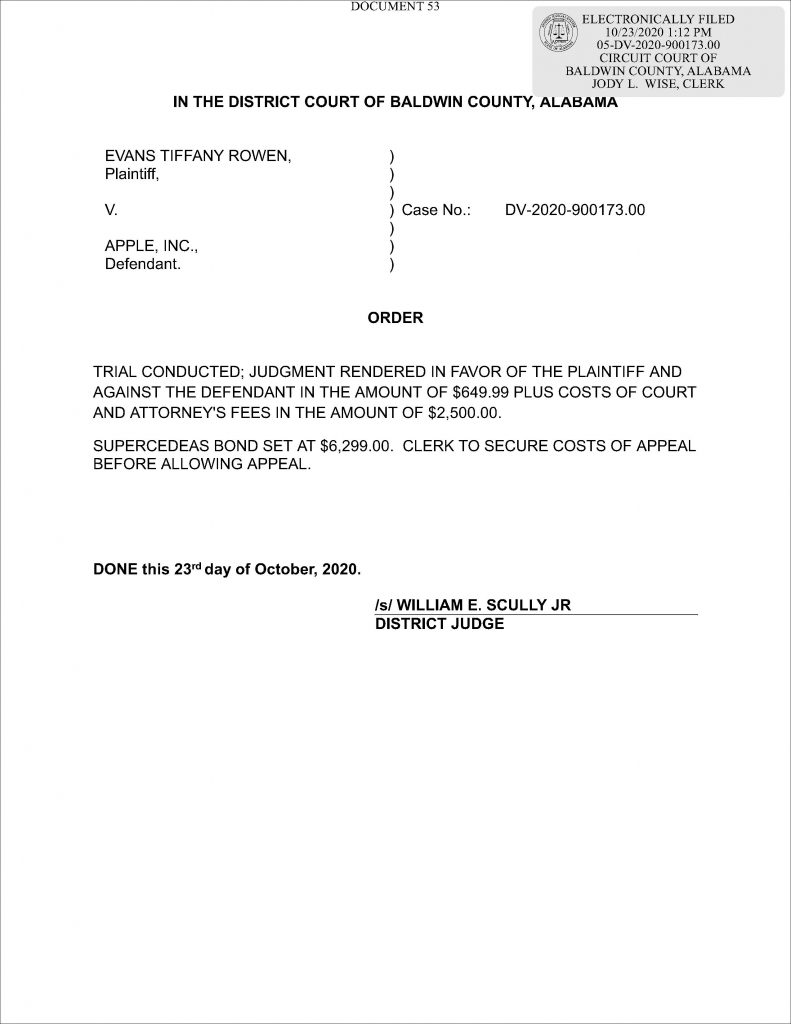

Thankfully, the trial judge wasn’t buying their story. At the end of the trial, he entered judgment against Apple for the cost of the iPhone, plus costs and attorneys’ fees. For most lawyers, a small judgment in a warranty case isn’t something to get excited about. But for me, it wasn’t really about the money. It was about holding a big corporation accountable for keeping its promises. And that’s just what we did. So if you or someone you know has a defective device and the manufacturer refuses to offer any help, call us. 251-272-9148.